Nowgol Mohseni’s artistic practice is rooted in rupture rather than continuity. Her work does not arise from abstract reflection on identity, but from lived experiences of exclusion, displacement, and distance from home. Born and raised in Iran, she developed as an artist within a cultural and political environment where personal expression is inseparable from social regulation. Rather than narrating this context directly or didactically, Mohseni allows it to shape her visual language over time. Her practice has evolved from confrontational, violence-centered imagery toward a quieter yet more structurally complex engagement with exile, memory, and aftermath.

Biography and Education

Mohseni’s disciplined approach to art began in Iran, where she attended an art-focused high school. Early training in figurative drawing and painting established a strong technical foundation and a lasting engagement with the human body. During this formative period, the body became a central site of inquiry—not only as form, but as something shaped by control, endurance, and external force.

A decisive shift occurred following Mohseni’s relocation to the United Kingdom three years ago, where she began formal studies in fine art with a focus on painting. Distance from Iran did not reduce the political urgency of her work; instead, it transformed how that urgency was expressed. Removed from immediate proximity to violence, she gradually turned away from depicting events themselves and toward their residue—what remains after rupture has already occurred.

Her working process reflects the self-directed structure of her art education in the UK, emphasizing conceptual independence and critical reflection. Largely self-taught in technique, Mohseni has worked across watercolor, charcoal, ink, oil, and acrylic. She increasingly favors acrylic for its speed and responsiveness, which allows her to register fleeting emotional states and unresolved memories. Drawing remains foundational to her practice, functioning not as preparation but as a site of experimentation and testing. Calligraphic elements occasionally appear in her works, anchoring her visual language in Persian cultural and linguistic traditions.

Literature and philosophy also play an important role in shaping her sensibility. Mohseni engages with thinkers such as Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, alongside writers including Dostoyevsky, Mahmoud Darwish, and Khaled Hosseini, whose reflections on war, displacement, and moral struggle resonate with her own concerns. Reading in Persian remains a deliberate act of cultural continuity, even as she works within an international academic environment.

Artistic Practice and Key Works

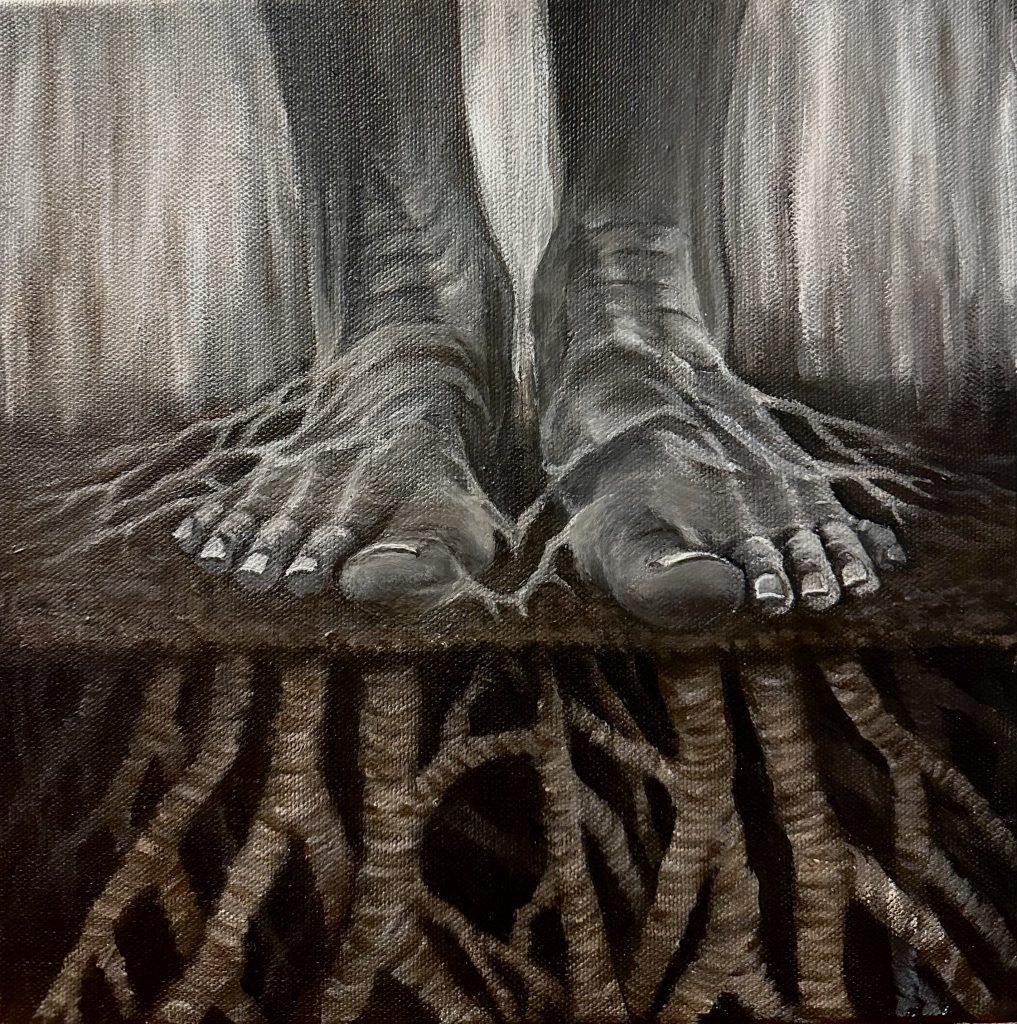

Coca-Cola (2022)

Acrylic and oil paint on canvas, 60 × 80 cm

Mohseni’s early paintings focus on the physical consequences of protest and imprisonment. Rather than relying on allegory or abstraction, she renders the body with anatomical precision—strained muscles, exposed ribs, and contorted limbs—emphasizing the material reality of pain. Coca-Cola stands as a singular and uncompromising confrontation with torture.

In this work, human bodies are forced into the rigid mold of a glass bottle, compressed and stacked without the possibility of movement. Transparency becomes a mechanism of cruelty: everything is visible, yet nothing is free. The bottle functions not as a pop-cultural reference, but as an industrial apparatus that standardizes, contains, and dehumanizes the body, while also operating as a phallic symbol of domination and torture. Mohseni does not extend this imagery into a series; the painting remains an isolated, declarative statement.

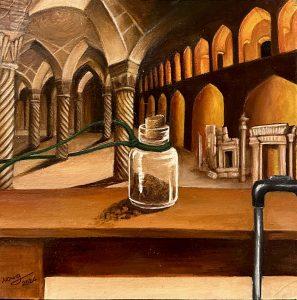

The A Jar of Soil Series

Voluntary exile became a condition shaping Nowgol’s perception of memory and space, leading to the ongoing A Jar of Soil series. The jar, containing soil from her homeland, functions as a recurring yet unstable motif—at times protected, at times displaced, at times emptied. It does not symbolize home itself, but the fragile attempt to carry fragments of it across borders.

Goodbye (2023)

Acrylic on paperboard, 20.5 × 20.5 cm

In Goodbye, the jar appears as a modest domestic object placed on a table before a receding architectural backdrop. The spilled soil becomes the painting’s most powerful gesture: irreversible, understated, and quietly devastating. Architecture functions here as memory rather than monument, with repeated arches suggesting cultural inheritance without authority or spectacle. The work is restrained, signaling Nowgol’s growing trust in absence and silence as carriers of meaning.

Dance (2026)

Acrylic on canvas, 133 × 70 cm

Dance presents collective movement as an unstable and unresolved condition. Although the figures appear engaged in shared motion, the space they occupy offers no sense of grounding or closure. Bodies are elongated, scraped, and partially erased, suggesting movement sustained through effort rather than ease. The surface resists fluidity; motion becomes endurance.

At the center of the composition, the jar—once associated with preservation—has been displaced and rotated horizontally. Open and exposed, it interrupts movement rather than organizing it. The figures strain past it, as if navigating an obstruction embedded within their path. A red trace of blood spilling from the jar introduces the presence of serious injury without spectacle, shifting attention from violence as an event to violence as endurance.

The work was inspired by Ahoo Daryaei’s public act of undressing in the streets of Iran as a protest against compulsory hijab—an act that reclaimed bodily autonomy through exposure rather than concealment. In this context, nudity functions not as vulnerability but as assertion. The collective movement in the painting echoes this gesture, reframing dance as defiance enacted through repetition and presence.

The work also enters into a quiet dialogue with Henri Matisse’s Dance, inverting its premise. Where Matisse imagines harmony and freedom as achieved states, Nowgol renders movement as contested and constrained. At a further remove, the painting resonates with images of mothers dancing on the graves of loved ones killed during the Iranian protests of 2025–2026, where mourning becomes a collective gesture of defiance—an insistence on presence under atrocity and totalitarian power.

Remains of War (2026)

Acrylic on canvas, 110 × 75 cm

This painting constructs an environment shaped by the aftermath of violence rather than its spectacle. The composition fractures into historical depth and contemporary emptiness. Red linear markings cut across the surface like forensic diagrams or laser guides, translating violence into geometry. In the foreground, a tipped glass, an emptied jar, and a slack green thread function as evidence. War is absent; what remains are traces and residues.

The Mythological Register

Alongside her architectural works, Nowgol has developed a parallel body of work operating in a mythological register, where exile is framed as a condition embedded in the body itself.

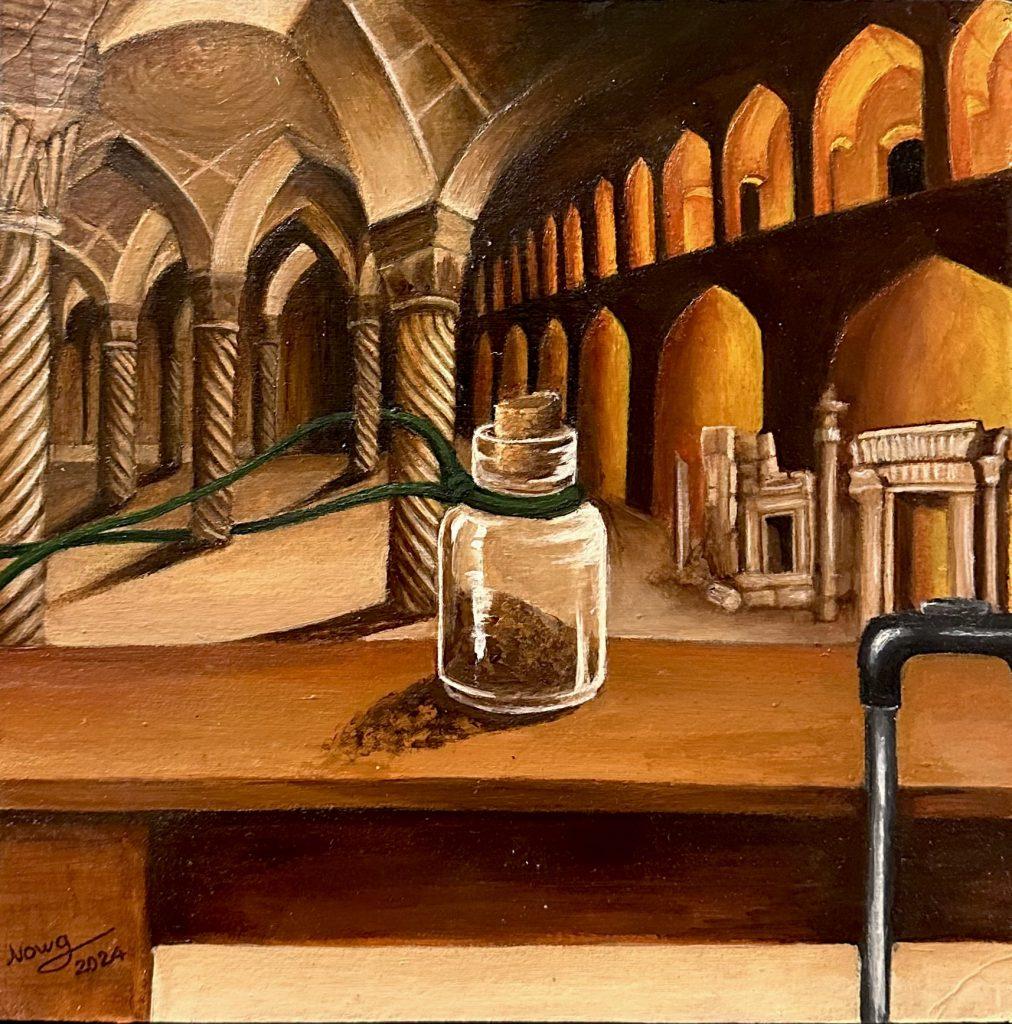

Escape (2023)

Ink and metal pen on paperboard, 14.5 × 25 cm

In Escape, multiple figures overlap and dissolve into one another, their bodies bound and constrained. They repeat a single reaching gesture toward a bird enclosed within a luminous boundary. Freedom is visible but structurally inaccessible. The dark, depthless background offers no horizon or exit, reinforcing containment. The work does not dramatize failure; it sustains exile as an unresolved collective condition.

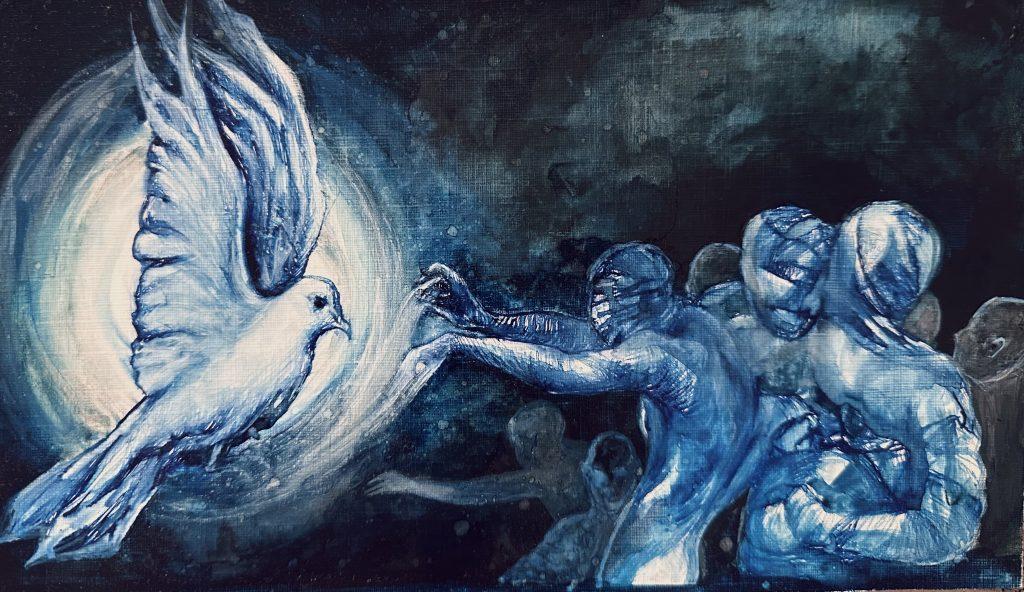

Our Roots (2024)

Acrylic on canvas, 25 × 25 cm

Our Roots reduces the body to feet dissolving into soil and root. Identity is no longer individual, but inherited and imposed. The roots bind as much as they ground, transforming origin into burden. The image operates as a contemporary myth, where belonging is inseparable from entanglement.

Conclusion

As Nowgol Mohseni approaches graduation and her London degree show, she continues to expand her visual language toward greater abstraction while retaining symbolic anchors. What distinguishes her practice is its refusal of resolution. Her work does not offer redemption or return, but dwells in tension—in what is carried, what spills, and what cannot be retrieved. Through restraint and structural clarity, personal rupture is transformed into a visual language that remains ethically alert, precise, and quietly forceful.

© The copyright of the text belongs to Dr. Davood Khazaie